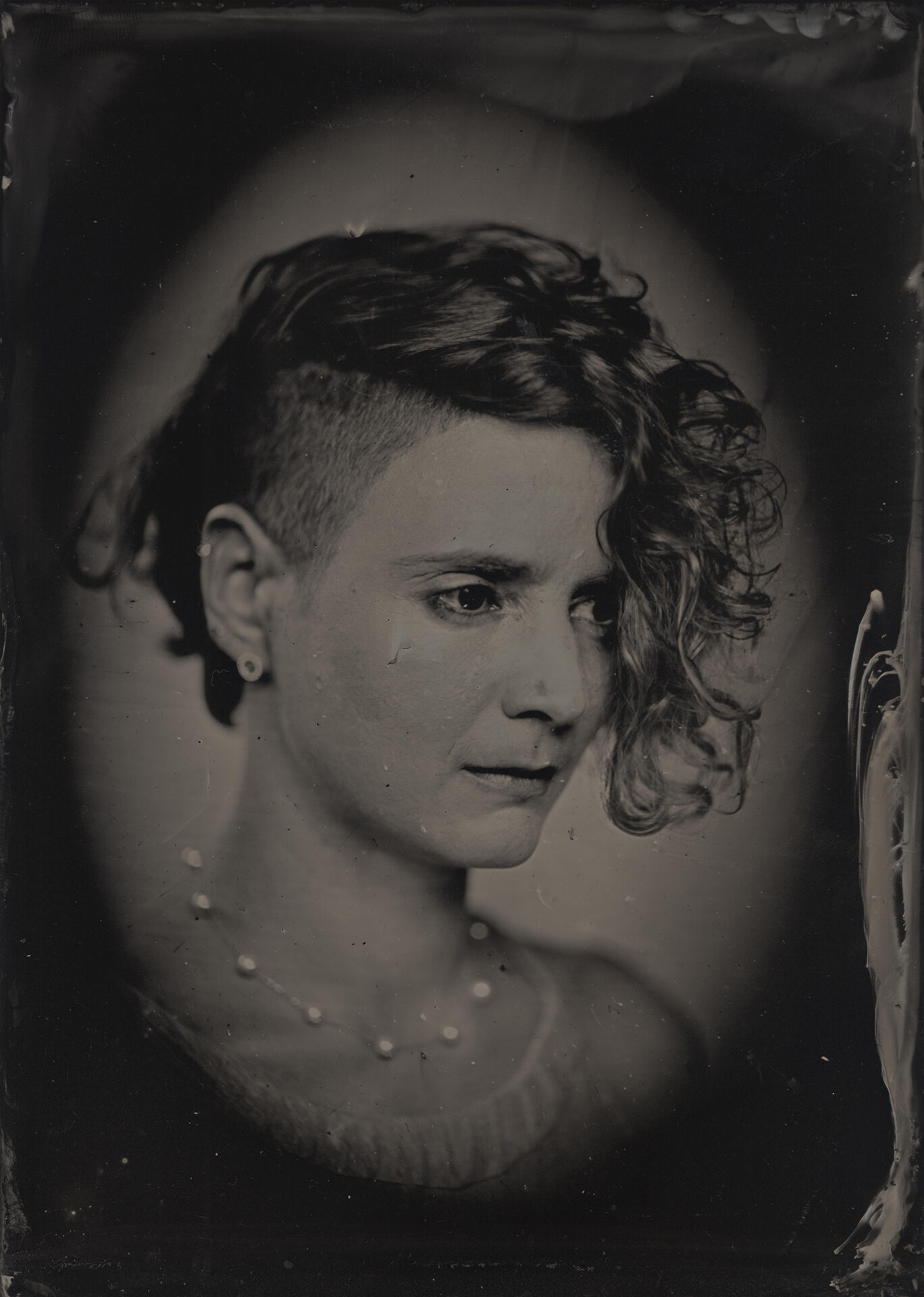

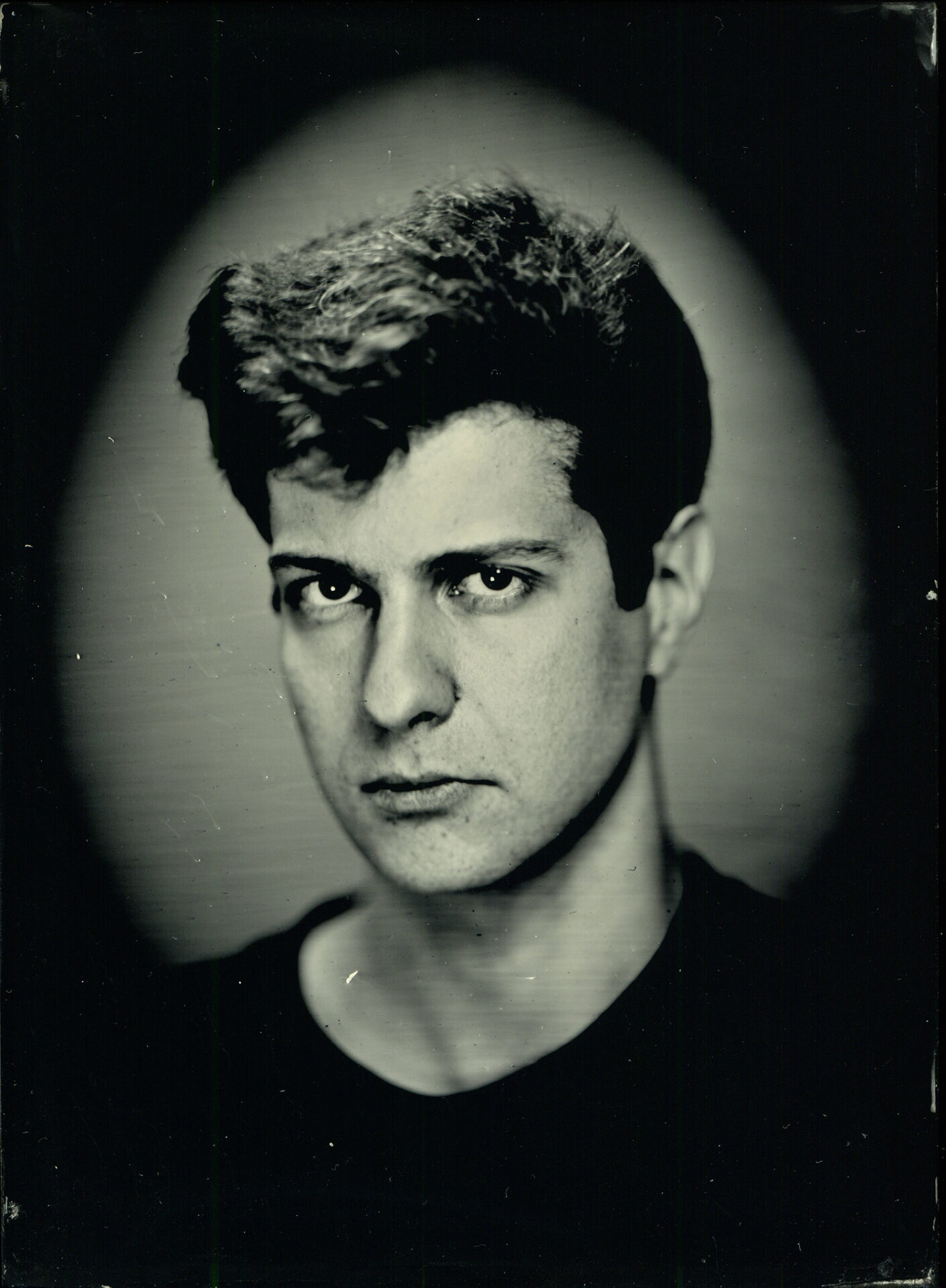

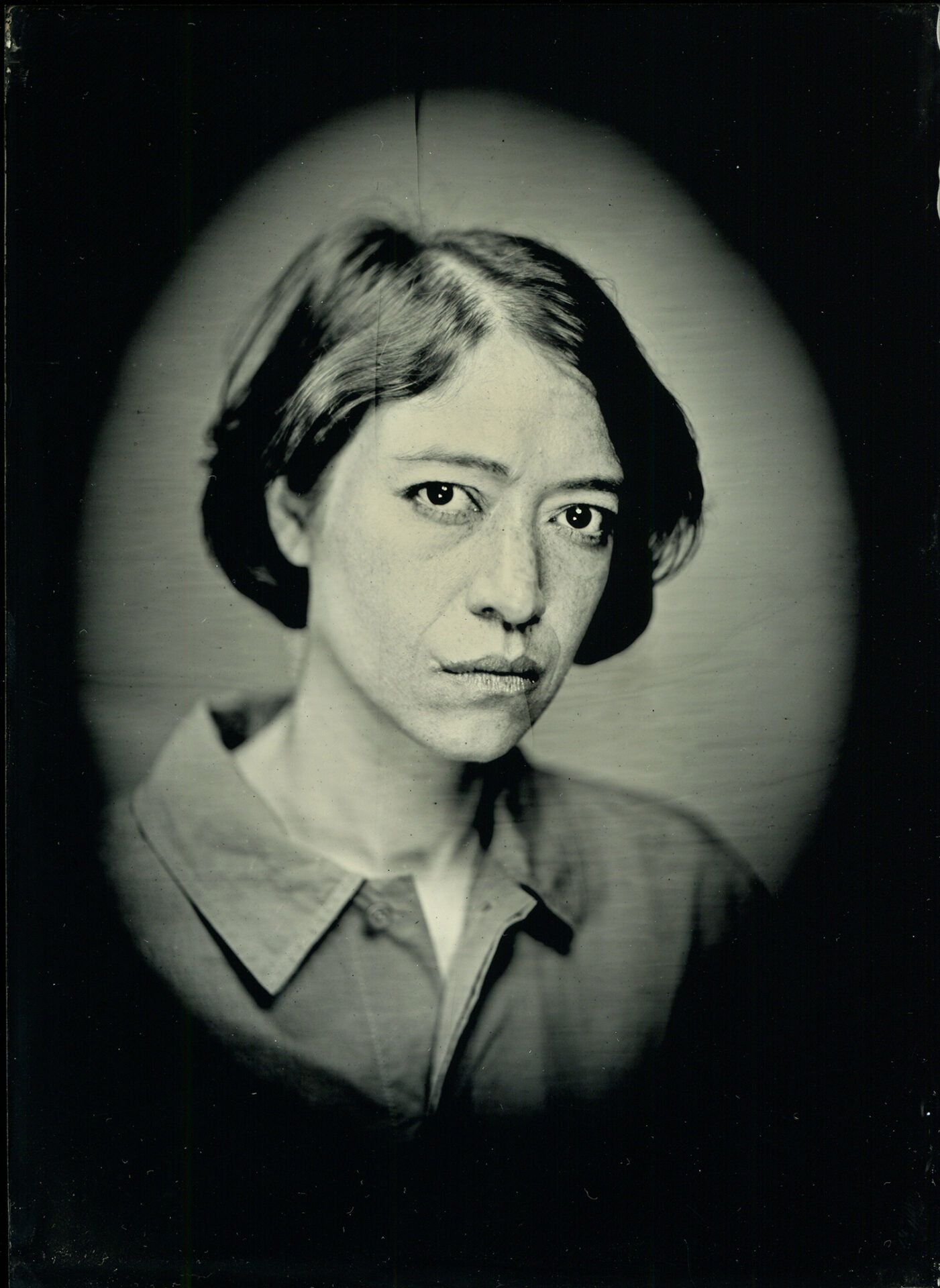

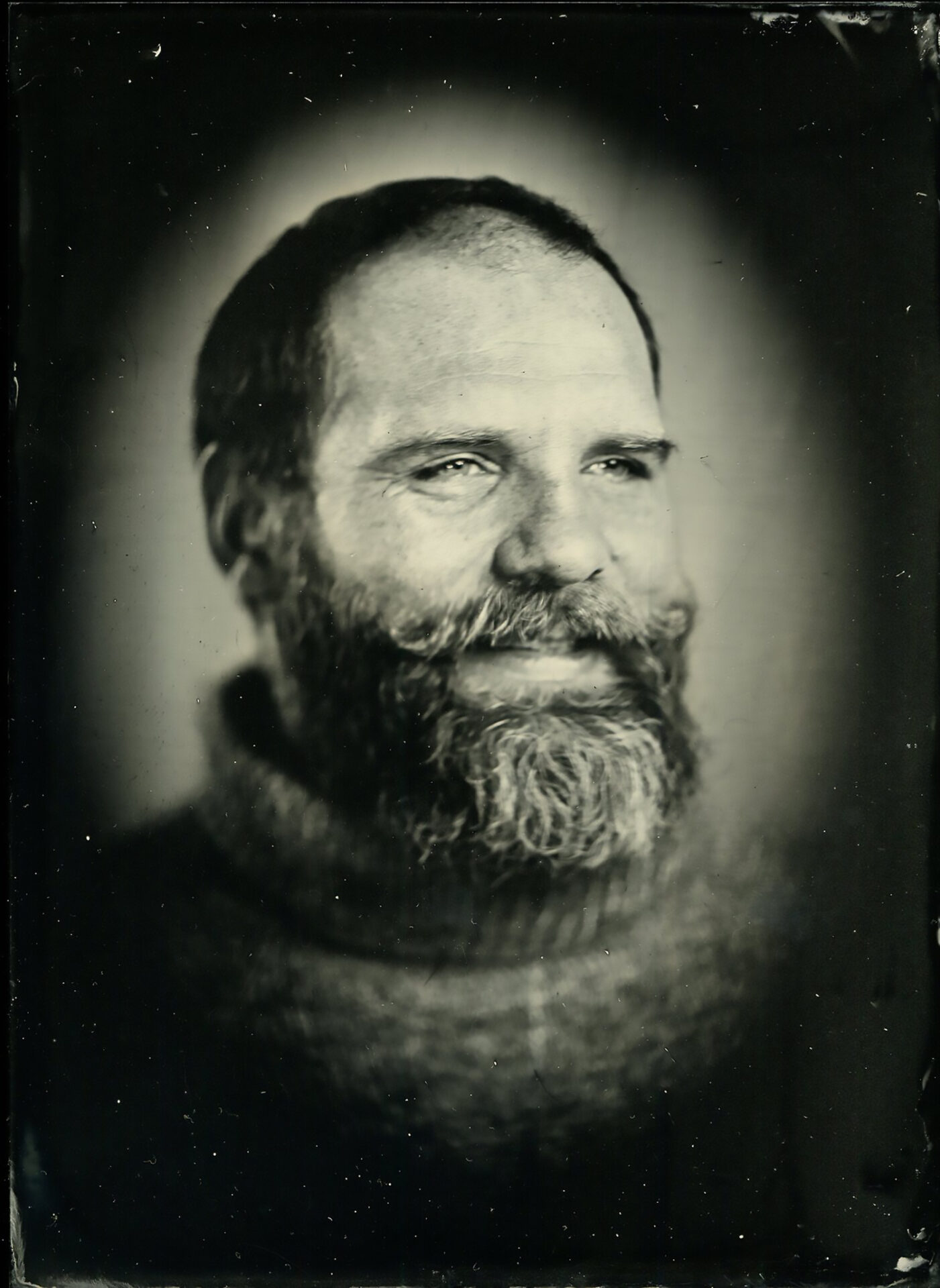

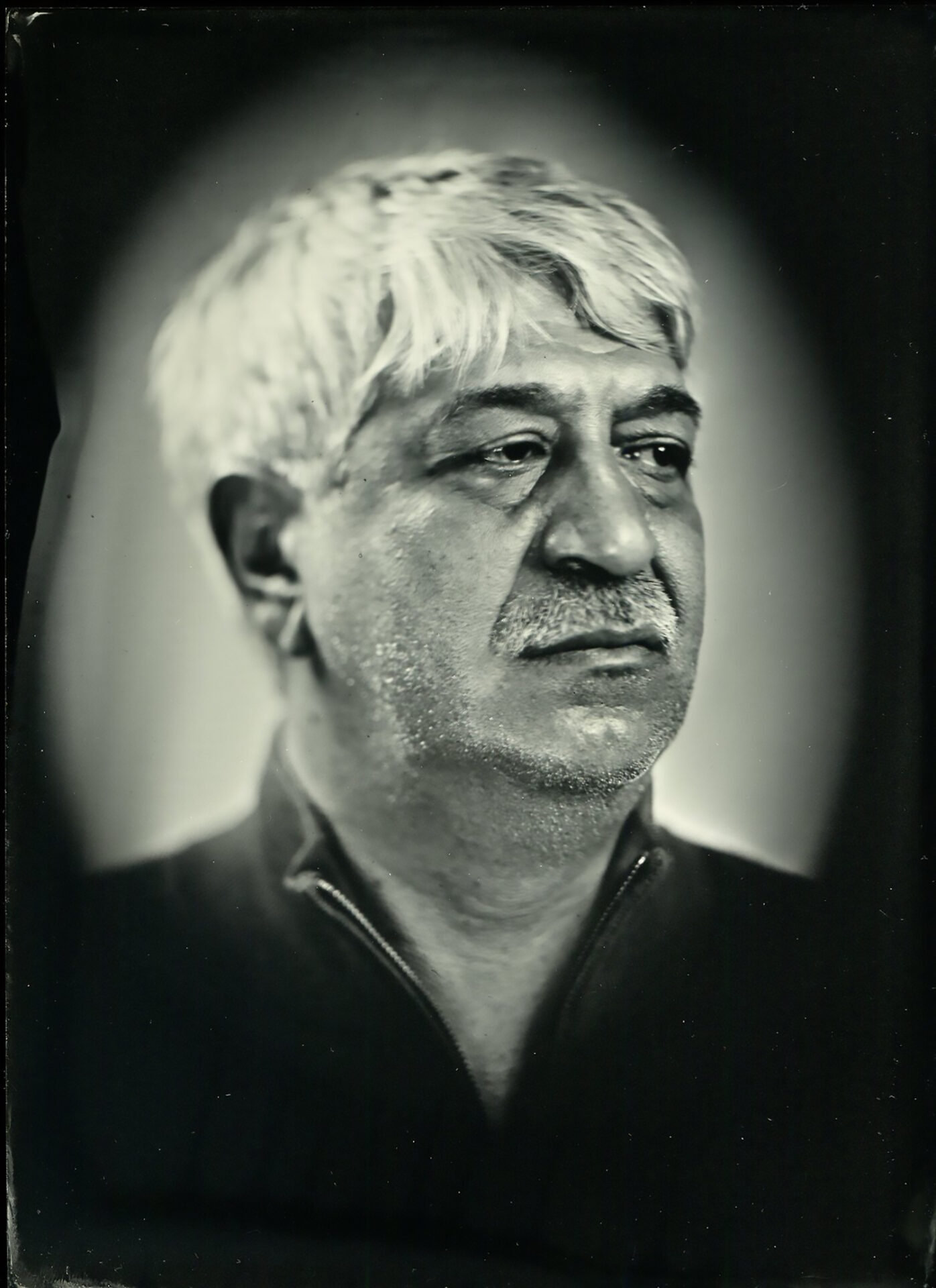

Facing Death (2017, 2018)

Ivan Lungin and Georgiy Keymakh’s Tintype Photo Studio

We believe creating a photograph for your gravestone while you are still alive is the right move.

Technical execution by Artemiy Perevoznik.

__________________

Georgiy Keymakh:

In our society, even thinking about death is frowned upon, let alone preparing for it. Buying life insurance, making a will—heck, even buckling your seatbelt—can bring up feelings of tension, irritation, or resentment. It seems like any thought about death is seen as a bad omen nowadays.

In light of all that, we decided to make these photographs in advance for two reasons:

The first is purely practical. The deceased leaves their loved ones with such a mess of problems that nitpicky details like a memorial portrait just might lie beyond the scope of their remaining energy.

The second reason is that we wanted to undertake some kind of rite of preparation for death. In a way, we are not only getting the opportunity to look at our own gravestones; this is a chance to make them look exactly how we want them.

Why did we choose this particular technology?

A tintype is an instant photograph made on tin plates that are coated with a solution of silver salts in collodion. It is one of the earliest photographic processes, and it is especially notable for the one-of-a-kind, unalterable, mirror-like images it creates.

Photography distinguishes itself from drawing or engraving in one essential aspect: veracity. This veracity may be approximate or sometimes unreliable, but nonetheless, as a rule, it is real.

Contemporary photography has so little in common with this elemental essence of photography that one could say it’s not even really photography anymore, that it lacks this authentic foundation.

We decided that tintype is the most suitable technique to carry out our particular task for several reasons:

-It is one of the most direct methods of producing a photographic image. It cannot be retouched, replicated, or cropped, and the image must be developed instantly.

-We find this technology to be beautiful. The silver on the brighter areas and the glossy black enamel in the shadows, the complete absence of “grain,” such a small depth of field, the reflectivity of the portrayal, the artifacts and stains, the long exposure and old-fashioned optics—all of this is very close to our hearts.

-Historically, tintypes have long been closely associated with death:

First, soldiers often had tintypes taken before leaving for the front during the American Civil War.

Second, photography used to be a mystical process surrounded by superstitions. People believed that being photographed steals your soul, that ghosts could appear in photographs, and even that you could affect someone remotely through a photograph of them.

__________________

Ivan Lungin

People get a lot of silly ideas about death, and those ideas are often completely practical in nature, not metaphysical at all. I have already faced clinical death, and I see nothing extraordinary at all in that event. One of these ideas got firmly stuck in my head about eight years ago. For some reason, I had a strong urge to go and get a portrait made for my own gravestone and store it away somewhere until better times. Oddly enough, moving from word to deed turned out to be fairly complicated: like all normal people, I always found more important things to do. Not long ago, however, Gosha Keymakh, an artist and a good friend of mine, called me with what was practically the exact same proposal. Unlocking your door when the herald of death comes to you is rather stupid, but I was actually quite pleased.

We decided to make a series of living portraits, beginning with ourselves. I wanted the photograph to represent the first encounter with death within life and, correspondingly, an acceptance of death, or at least a small reconciliation with the idea of it.

In the process of realizing this idea, things turned out to be even more heavily symbolic than we expected. Because the exposure is so long, anyone who poses for a photograph has to hold their breath for ten seconds. It’s not much, but even that short moment can be enough to feel, suddenly, just for a few seconds, that you are something of a potential corpse. Still warm, still thinking, but nonetheless conscious of the inevitability of death.